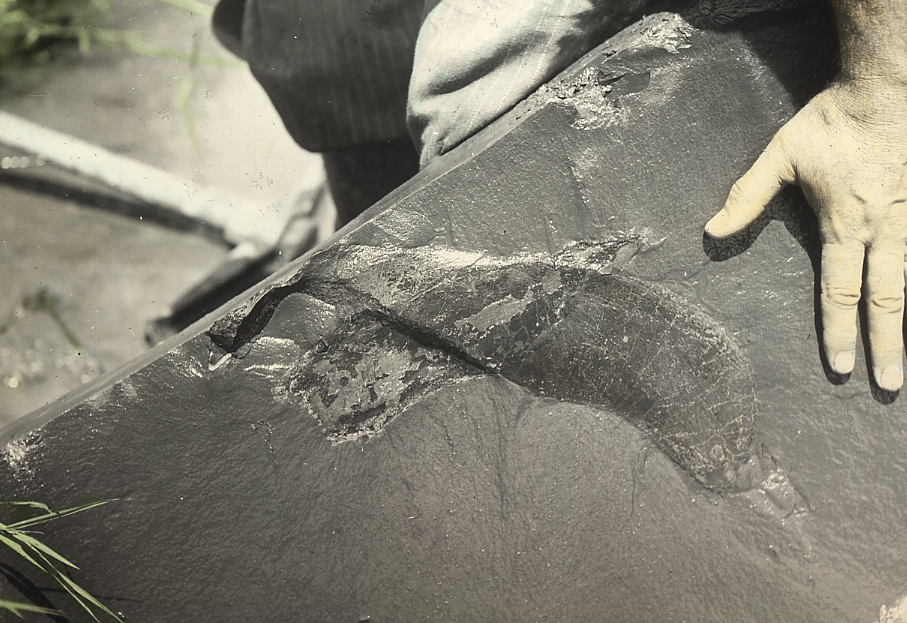

Here is my paper from the ASSC graduate conference, last month. I was privileged to this give on a panel with Mary Kate Hurley and Mo Pareles. The paper was given with this handout which contains images I reference near the end of the paper.

Where Wisps of Being Mingle:

Theorizing The Space of the Wræclast in Christ and Satan

I want to first invoke Joyce Hill’s call, now almost some 20 years in the past, to attend to the divergent ‘Germania’ and ‘Latinia’ approaches to the so-called Old English ‘biblical poems’ (an article now anthologized in R.M. Liuzza’s Junius 11 Casebook). Yet I would direct us not to Hill’s call for a sober empirical attempt to correct our biases in approaching ‘evidence,’ but to the theoretical implications which appear in “the coming together of Germanic and Latin (Christian) cultures in medieval northwest Europe.”[i] Hill analyzed “the two extreme positions from which scholars in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries have approached the vernacular poetry of Anglo-Saxon England.”[ii] From out the earliest Germanic philology and antiquitarianism, feeding into a now infamous nationalism (that understandably continues to darken the sound of ‘philology’ in some quarters), the ‘Germania’ approach allowed that these poems “could be dismissed, as they frequently were, as at best dull paraphrases, deserving of comment only for a few passages, which critic after critic cites as evidence of a persistent Germanic spirit surfacing in the Christian subject matter.”[iii] Twenty years ago Hill could claim that “the biblical poems are obviously catching up,” but only at the cost being read almost solely in terms patristic traditions and Latin Christianity.[iv] I want to offer a reading of the Junius 11 Book poem Christ and Satan geared towards the political work of the poem—analyzing the production of a space that is political, or, rather, determinative of the political, operating a space at the historical, theoretical and literary confluence of Germania and Latinia.

I begin with this lengthy detour because I believe that reading Old English as a confrontation of Germania and Latinia forms the site of a particularly important crux of the west itself: a privileged site for deciphering the space of exile. The space of exile as such open a aporia deep within the ‘west’ and certain impending political disasters around the world. I refer to Giorgio Agamben’s now famous claim that the structure of sovereignty as a double exclusion resides in a figure taken from the Latin tradition and Etruscan law, the homo sacer. Yet, Agamben’s analysis of the structure of this relation to the one who is exiled will rely on a term whose Germanic linguistic origin Agamben sees fit to note (it is of such importance that I ask forgiveness for a long quotation):

If the exception is the structure of sovereignty, then sovereignty is not an exclusively political concept, an exclusively juridical category, a power external to law, or the supreme rule of the juridical order: it is the originary structure in which law refers to life and includes itself in it by suspending it. Taking up Jean-Luc Nancy’s suggestion, we shall give the name ban (taken from the old Germanic term that designates both exclusion from the community and the command and insignia of the sovereign) to this potentiality...of the law to maintain itself in its own privation, to apply in no longer applying...He who has been banned is not, in fact, simply set outside the law and made indifferent to it, but rather abandoned by it, that is, exposed and threatened on the threshold in which life and law, outside and inside, become indistinguishable.[v]

Now, Agamben insists that while we might view the task of sovereignty as an ‘ordering of space,’ the space of the exception remains prior to this ordering and always at the threshold of what constitutes an outside: “the state of exception opens the space in which the determination of a certain juridical order and a particular territory first becomes possible. As such, the state of exception itself is thus essentially unlocalizable (even if definite spatiotemporal limits can be assigned to it from time to time).”[vi] But even if this space is permanently un-localizable, or perhaps more importantly if it is, we have yet to decipher the structure of this space as such. So, what is the space of exile, and how is it structured? Given how much we mention exile as readers of Old English—in this corpus of literature that is at once on the edge of and in deeply within the west (geographically and temporally), it seems more than fitting to turn to Christ and Satan.

The Old English word wræclast, a masculine noun glossed by Bosworth-Toller as “an exile track,”[vii] despite being most easily associated with the Exeter Book elegies, occurs three times in the Old English poem Christ and Satan in the eleventh-century Manuscript Junius 11, making Christ and Satan the poem with the most occurrences of the word in a single poem of the extant corpus. Junius 11, of course, also contains Genesis A and B, Exodus, and Daniel, in that order. Christ and Satan is placed at the end of the manuscript and was added later, in multiple, different hands from the first three sections, almost tacked on to remaining folios of what began as a more majestic production, on the outskirts of the book itself in time and space.[viii] I am concerned here with the structure of the space named by wræclast, a word most often associated with the socially or politically defined spaces of exile in the Exeter Book, but which occurs in its highest density in Christ and Satan.

In the Exeter Book elegy known as “The Wanderer,” wræclast names a space one must wadan[ix] (go through, wade through), and also a track or space that commands the complete attention of one’s being, as “warað hine wræclast” (the exile’s path holds him/awaits him/keeps him).[x] Similarly, the speaker in the Exeter Book poem we call “The Seafarer” provides a self-description as an exile among “þe þa wræclastas widost lecgað” (those who follow the exile’s paths the farthest [out]).[xi] In Beowulf , we read that Grendel “wræclastas træd,” (tread on, trampled on the wræclast),[xii] suggesting that the clearly less- if not entirely non-human can move through this space.[xiii] In a more clearly political context, the Old English Death of King Edward, describes how the king, following the defeat of Æthelred by Cnut, “wunode wræclastum wide geond eorðan”[xiv] (dwelled in the exile’s paths widely through the earth).

What is common to all of these uses of the word is the suggestion that the wræclastas is a space, be it landscape or seascape, to where one is cast out from a community and it’s safety, where one is alone, and through or around which one constantly moves—exposed as lonely and without shelter in a vast space. In the above examples, the space is wide, is described as having space enough to wander, dwell, follow, etc. It is indeed Agamben’s threshold where life and law become indistinguishable: the wanderer bereft of any social space for whom any politics would consist in survival; the seafaring pilgrim who, ironically nihilistically, renounces this world as the space of his proper being; the outlawed sovereign king; the monster. Their space is structured in a way such that it both allows and demands movement—the term paired with a verb connoting a sense of travel, wandering, and specifically wandering through a large lonely space. The word thus seems to retain a strong trace of the second part of its compound structure: last (es), a noun meaning “a step, footstep, sole of the foot, track, trace.”[xv]

Satan then, in relation to the sovereign God by placement in lawless space, by the ban of God, would seem to occupy a quintessentially exilic space. And one might initially account for the occurrence of wræclast in Christ and Satan as an appropriation of the mode of the soliloquizing complaint employed by the poets of the Exeter Book elegies, as Robert Hasenfratz has also observed.[xvi] The whole first section of the poem is of course filled with the complaints of Satan and the fallen angels whose cunning and sense of being wronged might even rival that of Milton’s Satan. The first appearance of the word is in one these complaints by Satan, very much in the mode of an elegy. He says that he must: “hweofran ðy widor,/ wadan wræclastas” (roam/turn about widely,/ travel the exile-path).[xvii] Satan’s verb-phrase emphasizing strenuous travel and space is perhaps underscored by the common but still strange plural appearing wræclastas, as if the space is not continuous, but a whole mess of paths. By saying wadan wræclastas, Satan attempts to frame his speech-act to register as that of a lonely and widely wandering exile, demanding the more sympathetic affection we are more willing to lend to the Wanderer. Yet, 20 lines before this initial use of this term, Satan first laments fixity as part and parcel of how his place of torment is structured: “þis is ðeostræ ham, ðearle gebunden/ fæstum fyrclommum; flor is on welme/ attre onlæd” (This dark home is tightly bound/ with fast fire-bindings, the floor is of flame/ kindled with venom).[xviii] Satan cannot in fact wander through the space he names as wræclast even if he wants to in order to hide from the shame of his sin—as the hall is, to him, relatively narrow. Satan claims “Ic eom limwæstmum þæt ic gelutian ne mæg/ on þyssum sidan sele, synnum forwundoed” (I am of such a size that I may not hide/ in this wide hall, totally wounded/stained by sin)[xix] The second time the word appears, Satan is obliged to say that he dwells there in a way characterized by fixity: he explains that “ic geþohte adrifan | drihten of selde,/ weoroda waldend;| sceal nu wreclastas/ settan sorhgcearig, | siðas wide” (I designed to drive the Lord from the throne/the hosts of Ruler; I must now anxious-sorrowing, settan the exile’s paths, the wide ways)[xx]. Satan must “settan,” which can mean “to dwell,” but also, dwelling with the sense of fixity, as in “to establish” or “to set up.”[xxi] These statements are marked strongly by the first person pronoun, as trustworthy or untrustworthy testimony about the very being of Satan, which in turn reflects something about the space he is in. So the wræclast names the space in which Satan dwells, (at least as Satan names it) but unlike in any of the Exeter Book occurrences, Satan describes this space as a structure that can be established in fixity. Remember, he has described it as a kind of shelter, or sele (hall)—implying that the structure of the place wræclast names might be thought otherwise—to the extent that the wræclast could consist of a static ‘home,” with a “floor,” even if this floor is constructed of flame and torment. How is it that Satan is exposed, to what is his being exposed in the sense belonging to the exile under the ban of the sovereign (God), if he is in a narrow shelter (relative to his large size) and not a wide sea or fen?

Satan’s being is exposed to the other beings in this narrow fixed space, and to the subsequent painful dimming of the boundaries of his being as it mingles with that of the others and the structure of the space itself. For, the third occurrence of wræclast reminds us that the fallen angels also dwell in this place, as is it is in their speech that they explain “þæt wræclastas wunian moton” (We should dwell in the exilic space).[xxii] That the demons speak at all in the poem reminds the reader that Satan’s speeches and uses of wræclast are in dialogic relation to those of the fallen angels, as the fallen angels use this word in a speech dialoging with those of Satan. These fallen angels dwell there, like Satan, because, as they say, “we woldon swa/ drihten adrifan of þam deoran ham”[xxiii] (they would have driven the Lord out from that precious home)—they would have exiled God. This occurrence of wræclast in a dialogue, naming the space in which that very dialogue occurs, suggests that the space is structured in a much less ‘lonely’ way than habitually thought. Perhaps Satan and his demons intentionally ‘misuse’ the term, trying to garner sympathy as if in they were in the plight of the lonely wronged exile and not would-be cosmic Sygbryt’s (who the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells us that Cynwulf drove out of his lands for unjust deeds). But the sheer density of the term’s occurrence in Christ and Satan seems to me to suggest that a reader would have been expected to have the capacity to understand the term in this context, even if ironically. So it is worth asking what the term would mean in this case, even if Satan and the fallen Angels invoke it infelicitously, without the proper political authority, or with intent to deceive.

This relationship between the multiple beings inhabiting this particular space and the structure of the space itself would then call for further re-thinking of exilic space in terms of how the space structures the relations of these beings to each other. In Christ and Satan, this indistinction between inside and outside (identified by Agamben as the topos of the ban) seems to extend itself to the difference between a space and beings that inhabit it. [xxiv] The fallen angels who themselves occupy the space also constitute it as a world for Satan. Satan himself identifies part of the place’s torment for him in complaining that “hwilum ic gehere hellescealas,/ gnornende cynn”[xxv] (Sometimes I hear hell-servants,/ a mourning kin). In this wræclast, some beings are fixed in space, but the distinction between what constitutes the place/space, and what inhabits it is confused or diffused.

So, the wræclast, as a place of exile, or exile-as-punishment for outlawry, may generally name a space understood less as one through which one can or must move, so much as a space in which an unclear relationship between space and beings, and beings and beings, is recognized as part of the structure of what wræclast itself names. In Christ and Satan, instead of a place to freely and widely wander in a romanticized conception of exilic space, Satan uses the term for a space of torment recognized more by its relation to torment and punishment, its relation to how relations function inside this space, and how the relation between space/landscape and Beings dissolves.

Agamben invokes his homo sacer as bare life, a category to which we might assign a wispy sort of ontology, a kind of being in relation to juridical structures only in its non-relation and whose being if it indeed has being in a rigorous sense—this being has at best a dim sort of ontological status. But the exiles of the wræclast—as it appears most densely in this early Germanic language text that is nonetheless the confrontation of that Germania with the theology of Latnia—the being of these exiles is even less than wispy. These beings are themselves part of the structure of the space that defines their being, their cries flitting painfully into and out of one another. The space is as much constituted by static wisps of beings whose boundaries between each other are thin and overlapping as it is by place.

As such, wræclast names a space whose structure in relation to the Beings that inhabit it must be thought in itself as a primordial ground for thinking categories of ‘life,’ and ‘the political.’ The trick, with Christ and Satan, is to think the word in this manner when reading an ostensibly theological poem. The difficulty of understanding this term perhaps reveals the urgent importance of the politics and theology enunciated by the confluence of Germania-Latina in Old English poetry. The exile, the transient of the west, is today increasingly defined in some cases not by movement and migration, but by being inscribed in a lack of freedom of movement, identified with the condition of the place itself: I cite the atrocious restriction of movement by the Israeli army during the current/recent war in Gaza, or the debacle of GTMO. To illustrate this crux of the west, unconcealed from within a strange Old English poem, I would even risk rather recklessly appropriating as images commensurate with that of the space of exile in Christ and Satan, these images from Alfonso Cuarón’s Children of Men, of paperless people in cages at the train station, whose structure of exile is made of each other, and whose status, fixed in place in their tiny wræclast among the other exiles leaves them barely encounterable to the hero of the film, much less the viewer for whom they structure only a ‘background’ image. So how do we relate to, or speak of, this space of exile, if its inhabitants so mingle, if they are under a ban which, in Agamben’s words, demands of us that we “put the very form of relation into question and to ask if the political fact is not perhaps thinkable beyond relation...”[xxvi] These questions arise, after all, from the complaints of a Satan whose use of the word wræclast we, on the one hand, should simply not believe as a felicitous use of the term. He may, after all, be trying to frame himself as inhabiting the space of exile to garner sympathy. But, if hell, if the exiled being, is simply inaccessible to our critical thought, presenting us with the threat to the western conception of ‘relation’ itself in the play of presence and absence, accessibility and inaccessibility, then who is it that will name the space of exile and her relation to it? Satan’s crafty complaint at once reveals that exilic space is better understood by the ontological status of its inhabitants than by its shape and size (as an Old English Satan struggles against his own language, revealing the limitations of the suffix last); but reveals also that insincere naming—naming a space with a name that the named space exceeds negatively, speaking about a space or territory without the political authority to do so—is the only speaking that can actually identify exile properly. If it is this convoluted concept of relations to language that we need in order to read the space of exile in Old English poetry, or in any text for that matter, then philology—a discipline trained to read agreements, kinships, influences, rhetoric, etc.—has, at the moment, a pressing task—deciphering perhaps not representations of space and individuals, but the (actual, not the mimetic) relation between the two itself in the realm of the political.

[i] See Joyce Hill, “Confronting Germania Latina: Changing Responses to Old English Biblical Verse” in The Poems of Junius 11: Basic readings, Edited by R. M. Liuzza (London: Routeledge, 2002) pp. 1-19.

[ii] Joyce Hill, 1.

[iii] ibid., 5.

[iv] ibid., 6.

[v] Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995), 28.

[vi] ibid., 19.

[vii] Bosworth and Toller, An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary (hereafter as Bosworth-Toller), s.v. “wræclast.”

[viii] George Philip Krapp, Introduction, The Junius Manuscript, ASPR 1(New York: Columbia University Press, 1931), p. xii.

[ix] The Wanderer, in The Exeter Book, ASPR 3, Edited by Elliott Van Kirk Dobbie and George Philip Krapp (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936), 1.

[x] ibid., 32.

[xi] The Seafarer, in The Exeter Book, 55.

[xii] Beowulf, in Beowulf and The Fight at Finnsburgh 3rd Ed., Edited by Fr. Klaeber (Boston: D.C. and Heath, 1950), 1352.

[xiii] This would of course not surprise a reader of Boethius, who comments on the criminal, a status which often is the cause of the exile’s state (though notably not with the wanderer), that “So what happens is that when a man abandons goodness and ceases to be human, being unable to rise to a divine condition, he sinks to the level of being and animal,” from The Consolation of Philosophy, Translated by Victor Watts (London: Penguin, 1966, Revised Ed. 1999), 94.

[xiv] The Death of King Edward in Anglo-Saxon Minor Poems, ASPR 6, Edited by Elliott Van Kirk Dobbie (New York: Columbia University Press), 15.

[xv] Bosworth-Toller, s.v. “last.”

[xvi] See Robert Hasenfratz, “The Theme of the ‘Penitent Damned’ and its Relation to Beowulf and Christ and Satan, Leeds Studies in English, New Series 21 (1990), pp. 45-69, see especially p. 54. Hasenfratz actually attempts to refine and understand sympathetic responses to the Satan of Christ and Satan like Margaret Bridges who finds, according to Hasenfratz, that Satan “has become the figure of pathos like the exiled Wanderer” (45).

[xvii] Christ and Satan, in The Junius Manuscript, ASPR 1, Edited by George Philip Krapp (New York: Columbia, 1931), 119-120.

[xviii] ibid., 38b-40a. See also 101b-103a: “Hær is nedran swæg,/ wyrmas gewunade. Is ðis wites clom/ feste gebunden” (Here is the sound of snakes, and serpents dwell/ This binding of torment is/ bound fast).

[xix] ibid., 129-130.

[xx] ibid., 187-189.

[xxi] Bosworth-Toller, s.v. “settan.”

[xxii] Christ and Satan, 257.

[xxiii] ibid., 254b-255.

[xxiv] Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer: Soveriegn Power and Bare Life, Translated by Daniel Heller-Roazen (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998), p.28.

[xxv] Christ and Satan, 132-133b, (Bosworth-Toller does not gloss hellescealc, but does gloss scealc, first as “servant.”)

[xxvi] Agamben, Homo Sacer, 29.