This is bit, extended a smidgen and adapted for being out-of-context, currently leading off the project outlined below in "a sample of current labors."

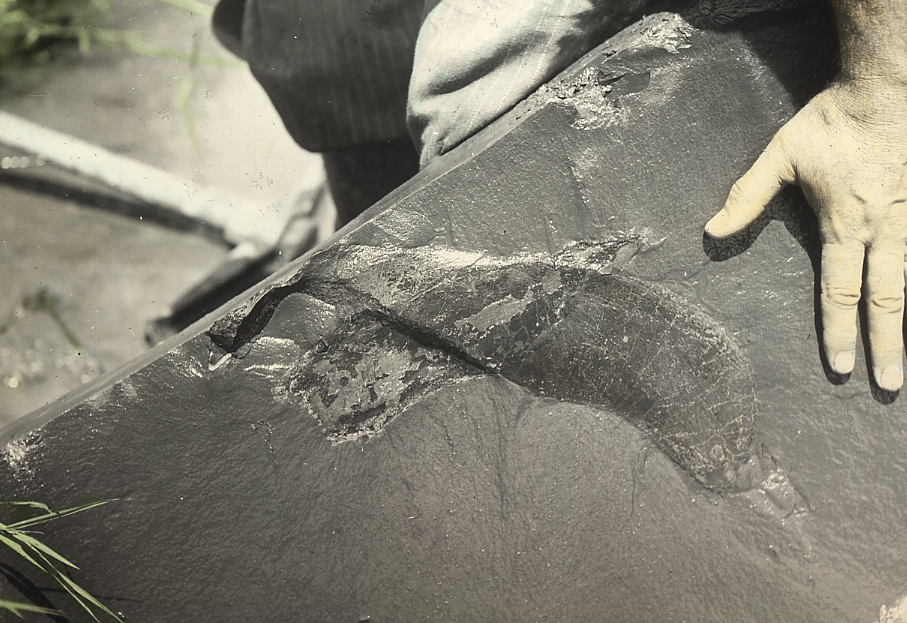

From “an old man in a dry month” in T.S. Eliot’s “Gerontion”— from this homophobic and anti-Semitic voice, who fears the sexual virility and spiritual (un)orthodoxy of “Christ the Tiger” coming “in the juvenescence of the year”—, from him we read, “Think now/ History has many cunning passages, contrived corridors/ And issues, deceives with whispering ambitions/ guides us by vanities.” To this man, and perhaps to Eliot, this is a horror (although perhaps Eliot is only horrified that this man cannot negotiate such passages and make something Historical of his modernity). History is perhaps most obviously implicated in an implied metaphor of a town, or city, or fortress, or dungeon (complete with issues of sewage). To be deceived or stuck or lost or fixated at any one dank and dead corner would be awful. But, shift the image only slightly from its direct context, and this History can be read as a part or whole of a lover’s body, or even as a fetish-object when we might admit the text or History, and texts in their historicity, as potentially exerting a gravitational pull on the erotic and queer-loving affects of an historiographer. What I am trying to write about these days, is my thinking about the poem “Wulf and Eadwacer” in and as such a history that might be queerly, physically, loved and explored and touched. That is, I am making a statement of desire for “Wulf and Eadwacer,” and exploring what that means, on what it is predicated, and what risks are involved—when we link a potential way of writing history as an event of touching (that is, feeling the texture of the past)—an event of erotic pleasure, and if that pleasure might be thought as the ground of justice—of a kind of history- writing beyond the mimetic economy.

The image taken from Eliot and looked at with squinted eyes perhaps appears as the rectum of history, the penis, or the vulva of history with their corridors and issues, as the metaphor extends—or as a queerly ‘incomplete’ part or body: the corridors as a fetish or a deferral to linger on or in: to feel in a manner that provokes contemporary sexualities. This would elicit a practice of reading, a historiography, as a poetics. That is to say, a writing interested in provoking events (in the way that Caputo’s poetics of the kingdom provoke, in the manner intentionally analogous to Derrida’s future-oriented take on negative critique in Specters of Marx), not producing/representing knowledge. Exploring and lingering in these corridors, these issues, one may be deceived as to one’s location in space and time. But, what is important is not an accurate ability to produce exact knowledge of whereabouts, how we got there and how we will get out, but the pleasure of the feeling—both in terms of doing justice to the lover, and the reader.

Friday, November 30, 2007

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)